The Fragmented Reality of Modern Data

Although businesses today have access to more data than ever before, this abundance rarely delivers clarity. Information arrives from countless sources, often in incompatible formats and under inconsistent rules. Commodity price data illustrates this problem especially well. Government releases, public statistics, and exchange feeds all follow different standards and timelines, making direct comparison difficult. Rather than having a seamless resource, businesses must clean, reconcile, and maintain a patchwork of data before they can put it to use. By the time procurement teams reconcile sources, market windows may have closed, costing companies millions in missed hedging opportunities.

Commodities are at the heart of this challenge. They are the lifeblood of every product company: a brewer needs barley and sugar, aluminium for cans, and silica for glass; an electronics maker needs copper, plastics, and rare metals. Knowing the cost of these inputs, both today and over time, is essential for negotiating with suppliers, forecasting COGS, and protecting margins. That raises a deceptively simple question: where do you get reliable price information for these inputs? Where can you see what market participants are actually paying for a ton of aluminum, a ton of sugar, or a barrel of palm oil?

This article explores the fragmented landscape of commodity price data, the providers behind it, and the trade-offs businesses face when choosing their data sources.

A fragmented landscape

Unfortunately, there is no single, universal source of truth for commodity pricing data. On the contrary, the data provider landscape is deeply fragmented. No single provider covers every material you might buy, and there are huge differences in cost, ease of data access, reliability, granularity, governance, and timeliness between different providers.

Before exploring providers, let’s clarify the goal: procurement and finance teams want both historical and current spot prices for their commodities, for example, the weekly spot price of barley. Because prices emerge from countless bilateral trades, gathering trustworthy data is hard.

In practice, pricing data lives in three broad places:

- Public sources: governments, inter‑governmental organizations, NGOs, statistical bureaus, and research institutes.

- Market venues: formal commodity exchanges plus the brokers who execute trades, and the data aggregators that pool their feeds.

- Price‑reporting agencies (PRAs) & specialty providers: firms that create transparency in markets where formal price signals are weak or nonexistent.

Let’s examine each of these buckets in turn.

1. Public sources

Crude oil is the archetypal commodity benchmark. Every evening news bulletins flash the latest Brent or WTI quote, and real‑time prices scroll across trading screens, as crude trades in enormous volumes on highly regulated futures exchanges such as NYMEX and ICE. Millions of barrels change hands each day through standardized contracts, generating a continuous, transparent price signal that anyone, from a hedge‑fund analyst to a taxi driver, can look up in seconds.

That level of visibility is the exception, not the rule. In most other commodity markets, deals are struck behind closed doors (over-the-counter), invoices remain confidential, and price discovery is murky. Efficient price discovery (and price visibility) needs many active buyers and sellers who can see firm bids and offers simultaneously so that prices converge where supply meets demand and the bid‑ask spread narrows. Without broad visibility of quotes and trades, information becomes asymmetric, allowing players with greater market power, such as large processors, dominant distributors, or regional cartels, to dictate terms. This leaves smaller buyers guessing whether they are overpaying or underpaying.

Governments have stepped in to level the playing field. A milestone example is the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Market Service (AMS). In 1915, progressive‑era reformers in the United States worried that farmers were “price‑takers” at the mercy of large railroads, produce dealers, and meat trusts. The farmers had no information or market power to set the price at which they could sell their products. In a bid to change this dynamic and create a transparent market, the AMS issued its first pricing report. Since then, what started as a $50K experiment is now a global standard for agricultural market transparency. The USDA now freely publishes over 250K price reports each year.

Since that time, governments and publicly funded organizations have made huge progress in collecting and disseminating pricing information to the public. Some examples from around the world include:

- The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis economic database publishes prices and price indices for the world’s most traded commodities.

- The European Commission Agri‑Food Data Portal publishes monthly farmgate prices for hundreds of agricultural products.

- The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development publishes price indices for various commodities on its website.

Much of this data is gathered through producer/input price surveys, call‑around networks of market‑news reporters, or mandated information feeds from businesses. Most of the time, the data are freely available to the public under the Creative Commons license. The trade-off is that these portals are often clunky, and updates may only occur monthly or even less frequently.

2. Market venues

Compared with the vast array of products treated as “commodities” in practice, only a relatively small set of commodities trade on official, centralized exchanges. Famous venues include the CBOT (Chicago Board of Trade), NYMEX (New York Mercantile Exchange), LME (London Metal Exchange), and DCE (Dalian Commodity Exchange). Typical exchange‑listed products include wheat, barley, sugar, palm oil, cocoa, and aluminum.

There are around 100 exchanges worldwide, each of which tends to specialize. For example, the LME focuses on metals; the DCE on agriculture, plastics, and energy; and the NYMEX on energy and metals. Exchanges collect real‑time (or near real‑time) trade data as orders between buyers and suppliers are matched. While headline prices are often published on public websites or in news tickers, more detailed information, such as granular feeds, depth‑of‑book quotes, and historical tick data, is usually paywalled or otherwise difficult to access.

Alongside the exchanges, some traders and brokers facilitate deals between counterparties or execute trades on their clients’ behalf. Many specialize in niche commodities and maintain proprietary price books and other information, such as order sizes and liquidity, which rarely reach the public domain.

Because collecting, standardizing, and maintaining all these inputs is difficult and expensive, many organizations turn to data aggregators such as LSEG (London Stock Exchange Group) or Bloomberg. These platforms license data from exchanges, brokers, and traders, then aggregate it into a single terminal, API, or data feed. This provides a consolidated view across markets. Accessing these data requires a subscription fee, which can be quite high and scales with the breadth and timeliness of access. However, out of all the ways to track commodity prices, exchange-traded prices are usually the most up-to-date, detailed, and closest to the real market value.

3. Price-reporting agencies and specialty providers

Most products considered commodities are never traded on an exchange and aren’t tracked by public sources. They swap hands between individual buyers and sellers in bilateral trades. That is where price‑reporting agencies (PRAs) step in to create price transparency. Companies like Argus Media, S&P Platts, I.C.I.S., and Mintec survey dozens of market participants, reconcile transaction details, and publish trusted price indices. Robust methodologies, such as sampling minimum volumes, discarding outliers, and verifying counterparties, aim to create confidence.

PRAs often gather extra context, such as production volumes, plant outages, and logistics. Most occupy narrow monopolies. For instance, I.C.I.S. dominates European & North American chemicals, while Argus is synonymous with certain energy grades. Smaller specialists dig even deeper. For instance, EUWID focuses on cardboard and paper packaging materials, while Upply and Freightos cover transport costs across the globe, such as the cost to ship a container from Shanghai to Amsterdam.

Because PRAs spend a lot of time making sure the prices they report are not biased, a lot of companies also use these indices to benchmark the contracts with their suppliers. If the underlying index rises (or falls), the supplier’s invoice adjusts accordingly. Of course, this is only feasible in practice if both parties trust the index.

The big disadvantage of working with PRAs is that they charge staggering prices for their data, sometimes more than 100.000 USD per commodity for global coverage.

A word on geography

In general, if you purchase a commodity in a specific region, the price index should align with that region. Prices can differ significantly across regions due to supply dynamics, policies, product specifications, and logistics.

An illustrative example of this is the difference in butter prices between Europe and the US. Due to supply-side differences, US prices are currently dropping while EU prices remain high. I Record-high milk and cream production in the US has driven prices lower, while higher feed and energy costs and adverse weather effects have kept butter prices elevated in Europe.

However, if you want a regional price signal for every commodity, there is bad news: coverage is inherently uneven. Most commodities are produced or consumed in specific regions, or traded on specific exchanges.. Even PRAs cannot cover all markets, because the cost of building indices outweighs the value in smaller regions.

Trade-offs when choosing between providers

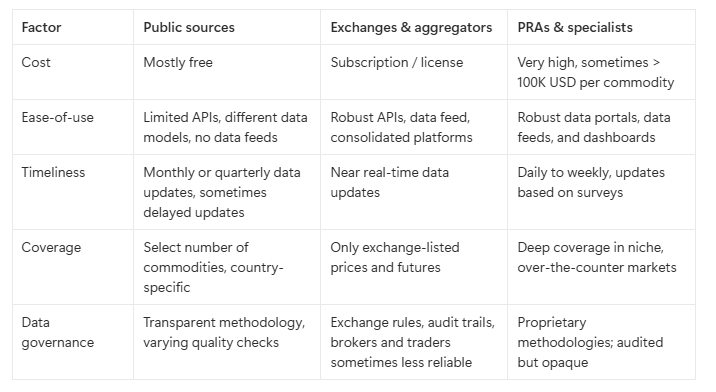

When choosing a data provider, there are five important factors to consider: the cost of getting the data, the ease of use, the timeliness of the data, the coverage, and the data governance and trustworthiness?

The table below gives an overview of these factors for each category of data providers:

Conclusion

Commodity‑price intelligence is inherently fragmented. No single data source provides an overviewof every market, region, and product. Therefore, buyers must compile information from governments, exchanges, brokers, price‑reporting agencies, and niche specialists. Each provider has its own set of trade-offs. Cost, ease-of-use, timeliness, coverage depth, and datagovernance rigor rarely align perfectly, forcing procurement and finance teams to prioritize according to their own risk tolerance and budget.

Because there is no single source of truth, diversification is not a luxury but a necessity. Relying on one exchange feed or a single PRA leaves blind spots that can undermine negotiations, distort COGS forecasts, or conceal margin risk. The smartest businesses build blended data stacks, combining free public datasets, exchange feeds for real‑time color, and high‑quality PRA benchmarks for opaque niches. They also invest in robust data governance so that feeds are standardized, auditable, and ready for downstream analytics.

Yet assembling that mosaic is easier said than done. APIs differ, file formats clash, licensing terms vary, and onboarding new feeds can drain scarce analyst bandwidth. Even large corporations struggle to maintain clean pipelines, let alone extract timely insights.

This is where Predikt enters the picture

Predikt provides a wide range of out-of-the-box price indices, collected, processed, and standardized from numerous government and public sources. Through partnerships with leading data aggregators such as LSEG, Predikt also delivers a broad selection of exchange-traded commodity indices.

By unifying these diverse datasets, Predikt bridges the gap between messy data pipelines and actionable market intelligence. The result: procurement gains leverage, finance sees around corners, and leadership stays ahead of market disruptions.

Curious? Book your personalized demo and discover how Predikt can empower your decision making.

.png)

.png)